As we have discussed, a string is also a data type. However, strings have a special characteristic: the issue of character encoding.

Computers can only process numbers. To handle text, it must first be converted into numbers. Early computers were designed using 8 bits as one byte. Therefore, the maximum integer a byte can represent is 255 (binary 11111111 = decimal 255). To represent larger integers, more bytes are required. For example, two bytes can represent a maximum integer of 65535, and four bytes can represent up to 4294967295.

Since computers were invented by Americans, initially only 127 characters were encoded into the computer. These included uppercase and lowercase English letters, digits, and some symbols. This encoding table is known as ASCII (American Standard Code for Information Interchange). For instance, the encoding for the uppercase letter A is 65, and for the lowercase letter z it is 122.

However, one byte is clearly insufficient for processing Chinese characters; at least two bytes are needed. Furthermore, this encoding must not conflict with ASCII. Therefore, China developed the GB2312 encoding standard to include Chinese characters.

As you can imagine, there are hundreds of languages worldwide. Japan encoded Japanese into Shift_JIS, Korea encoded Korean into Euc-kr, and so on. Each country had its own standard, which inevitably led to conflicts. The result was garbled text appearing in documents containing a mix of languages.

Thus, the Unicode character set was created. Unicode unifies all languages into a single encoding scheme, eliminating the problem of garbled text once and for all.

The Unicode standard is continuously evolving, but the most commonly used encoding is UCS-16, which uses two bytes to represent a single character (four bytes are needed for very rare characters). Modern operating systems and most programming languages directly support Unicode.

Now, let’s clarify the difference between ASCII and Unicode encodings: ASCII uses 1 byte, while Unicode typically uses 2 bytes.

A in ASCII is decimal 65, binary 01000001.0 (zero) in ASCII is decimal 48, binary 00110000. Note that the character '0' is different from the integer 0.中 (meaning “middle” or “China”) falls outside the ASCII range. Its Unicode encoding is decimal 20013, binary 01001110 00101101.You can infer that to represent the ASCII character A in Unicode, you simply need to pad zeros in front. Therefore, the Unicode encoding for A is 00000000 01000001.

A new problem emerged: while unifying on Unicode solved the garbled text issue, if the text you are working with is primarily in English, using Unicode requires twice the storage space compared to ASCII. This is very inefficient in terms of storage and transmission.

Therefore, in the interest of efficiency, the UTF-8 (Unicode Transformation Format – 8-bit) encoding was developed. UTF-8 is a variable-length encoding that converts Unicode characters into 1 to 6 bytes based on their numerical value. Commonly used English letters are encoded into 1 byte, Chinese characters are typically encoded into 3 bytes, and only very rare characters are encoded into 4 to 6 bytes. If the text you are transmitting contains a lot of English characters, using UTF-8 encoding will save space:

| Character | ASCII | Unicode | UTF-8 |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | 01000001 | 00000000 01000001 | 01000001 |

| 中 | (N/A) | 01001110 00101101 | 11100100 10111000 10101101 |

From the table above, you can also see an additional benefit of UTF-8 encoding: ASCII encoding can actually be considered a subset of UTF-8. Therefore, a large amount of legacy software that only supports ASCII can continue to work under UTF-8 encoding.

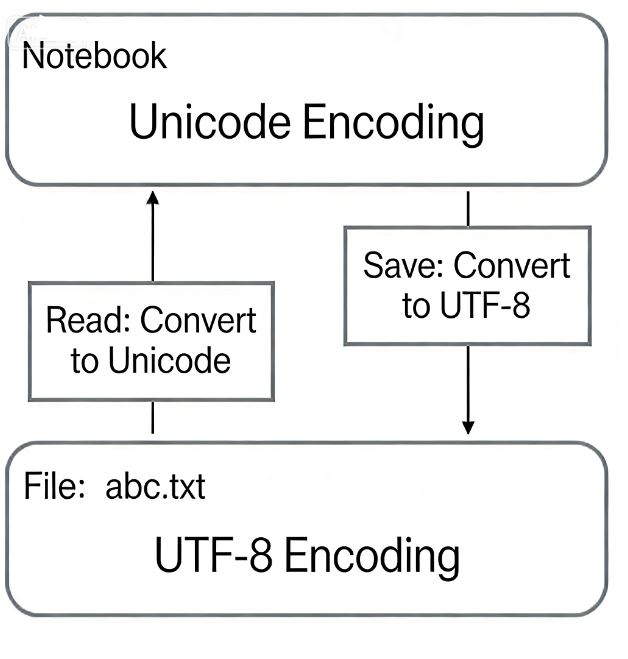

Now that we understand the relationship between ASCII, Unicode, and UTF-8, we can summarize the common character encoding workflow used in computer systems:

When editing with Notepad:

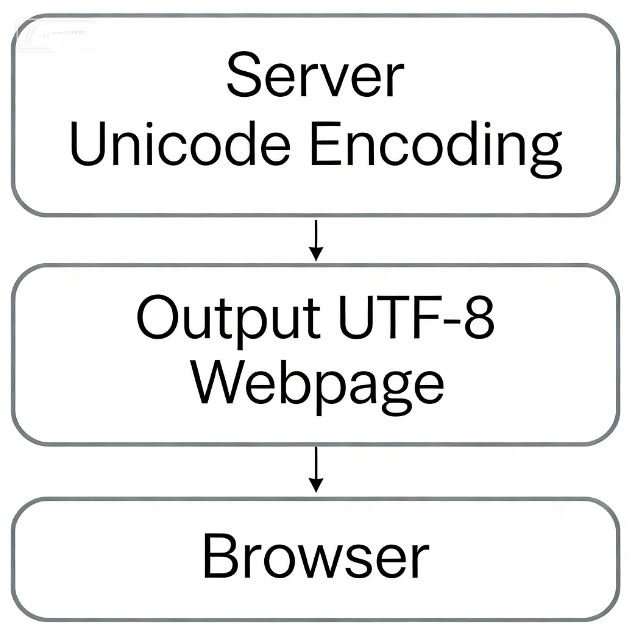

When browsing a web page:

This is why you often see information like <meta charset="UTF-8" /> in the source code of web pages, indicating that the page uses UTF-8 encoding.

Now that we’ve clarified the confusing issue of character encoding, let’s examine Python strings.

In the latest Python 3 version, strings are Unicode-encoded. This means Python strings natively support multiple languages. For example:

>>> print('包含中文的str') # String containing Chinese characters

包含中文的str

For encoding individual characters, Python provides the ord() function to get the integer representation of a character and the chr() function to convert an integer code back to its corresponding character:

>>> ord('A')

65

>>> ord('中')

20013

>>> chr(66)

'B'

>>> chr(25991)

'文'

If you know the integer code of a character, you can also write the string using its hexadecimal Unicode escape sequence:

>>> '\u4e2d\u6587'

'中文'

Both representations are completely equivalent.

Since Python’s string type (str) is represented in memory as Unicode, each character corresponds to a certain number of bytes. To transmit strings over a network or save them to disk, you need to convert str objects into bytes, which are sequences of raw bytes.

In Python, data of type bytes is represented using single or double quotes prefixed with b:

x = b'ABC'

It’s important to distinguish between 'ABC' and b'ABC':

str object.bytes object. Although their content appears the same when printed, each character in a bytes object occupies exactly one byte.A Unicode str can be encoded into a specified bytes format using the encode() method. For example:

>>> 'ABC'.encode('ascii')

b'ABC'

>>> '中文'.encode('utf-8')

b'\xe4\xb8\xad\xe6\x96\x87'

>>> '中文'.encode('ascii')

Traceback (most recent call last):

File "<stdin>", line 1, in <module>

UnicodeEncodeError: 'ascii' codec can't encode characters in position 0-1: ordinal not in range(128)

str containing only English characters can be encoded into bytes using ASCII, and the content will be the same.str containing Chinese characters can be encoded into bytes using UTF-8.str containing Chinese characters cannot be encoded using ASCII because the range of Chinese character codes exceeds that of ASCII. Python will raise a UnicodeEncodeError.Within a bytes object, any byte that cannot be displayed as an ASCII character is shown using the \x## escape sequence, where ## is the hexadecimal value of the byte.

Conversely, if you read a byte stream from a network or disk, the data you receive will be of type bytes. To convert bytes back to str, you need to use the decode() method:

>>> b'ABC'.decode('ascii')

'ABC'

>>> b'\xe4\xb8\xad\xe6\x96\x87'.decode('utf-8')

'中文'

If the bytes object contains undecodable bytes, the decode() method will raise an error:

>>> b'\xe4\xb8\xad\xff'.decode('utf-8')

Traceback (most recent call last):

...

UnicodeDecodeError: 'utf-8' codec can't decode byte 0xff in position 3: invalid start byte

If only a small portion of the bytes in the bytes object are invalid, you can pass errors='ignore' to ignore the problematic bytes:

>>> b'\xe4\xb8\xad\xff'.decode('utf-8', errors='ignore')

'中'

To calculate the number of characters in a str, use the len() function:

>>> len('ABC')

3

>>> len('中文')

2

The len() function counts the number of characters in a str. If applied to a bytes object, len() counts the number of bytes:

>>> len(b'ABC')

3

>>> len(b'\xe4\xb8\xad\xe6\x96\x87')

6

>>> len('中文'.encode('utf-8'))

6

As you can see, one Chinese character typically occupies 3 bytes when encoded in UTF-8, while one English character occupies only 1 byte.

When working with strings, we frequently encounter the need to convert between str and bytes. To avoid garbled text issues, you should always use UTF-8 encoding for converting between str and bytes.

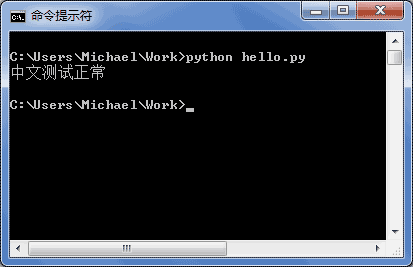

Since Python source code is also a text file, when your source code contains Chinese characters, you must ensure that you save the source code file in UTF-8 encoding. To instruct the Python interpreter to read the source code as UTF-8, we usually write these two lines at the very beginning of the file:

#!/usr/bin/env python3

# -*- coding: utf-8 -*-

Declaring UTF-8 encoding does not guarantee that your .py file is actually saved in UTF-8. You must also ensure that your text editor is configured to use UTF-8 encoding.

If your .py file is saved in UTF-8 and declares # -*- coding: utf-8 -*-, testing it in the command prompt will display Chinese characters correctly:

A final common task is how to output formatted strings. We often need to output strings like 'Dear xxx, hello! Your phone bill for xx month is xx, and your balance is xx', where the xxx parts change based on variables. Therefore, we need a convenient way to format strings.

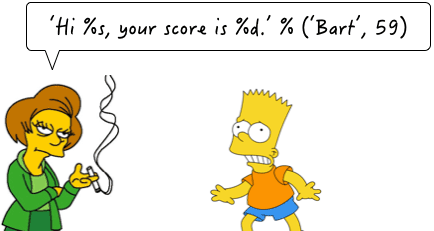

In Python, the formatting method is consistent with that of the C language, using the % operator. Here are some examples:

>>> 'Hello, %s' % 'world'

'Hello, world'

>>> 'Hi, %s, you have $%d.' % ('Michael', 1000000)

'Hi, Michael, you have $1000000.'

As you might have guessed, the % operator is used to format strings. Inside the string:

%s indicates a placeholder to be replaced by a string.%d indicates a placeholder to be replaced by an integer.You should have as many variables or values after the % as there are placeholders in the string, and they must be in the correct order. If there is only one placeholder, the parentheses around the single value can be omitted.

Common placeholders include:

| Placeholder | Replacement Content |

|---|---|

%d | Integer |

%f | Floating-point number |

%s | String |

%x | Hexadecimal integer |

When formatting integers and floating-point numbers, you can also specify padding with zeros and the number of digits for the integer and fractional parts:

print('%2d-%02d' % (3, 1)) # Output: ' 3-01'

print('%.2f' % 3.1415926) # Output: '3.14'

If you are unsure which placeholder to use, %s will always work. It converts any data type into a string:

>>> 'Age: %s. Gender: %s' % (25, True)

'Age: 25. Gender: True'

What if you need to include a literal % character inside the string? In this case, you need to escape it by using %% to represent a single %:

>>> 'growth rate: %d %%' % 7

'growth rate: 7 %'

format() MethodAnother way to format strings is to use the string’s format() method. This method replaces placeholders like {0}, {1}, etc., inside the string with the arguments passed in order. However, this method is generally considered more cumbersome than using %:

>>> 'Hello, {0}, your score improved by {1:.1f}%'.format('小明', 17.125)

'Hello, 小明, your score improved by 17.1%'

The latest method for formatting strings is to use f-strings, which are prefixed with f. Unlike regular strings, if an f-string contains {xxx}, it will be replaced with the value of the variable xxx:

>>> r = 2.5

>>> s = 3.14 * r ** 2

>>> print(f'The area of a circle with radius {r} is {s:.2f}')

The area of a circle with radius 2.5 is 19.62

In the code above:

{r} is replaced with the value of the variable r.{s:.2f} is replaced with the value of the variable s, and :.2f specifies a formatting parameter (retaining two decimal places). Thus, {s:.2f} is replaced with 19.62.Strings in Python 3 use Unicode, which provides direct support for multiple languages.

When converting between str and bytes, you need to specify an encoding. The most commonly used encoding is UTF-8. Python certainly supports other encoding methods as well. For example, you can encode Unicode into GB2312:

>>> '中文'.encode('gb2312')

b'\xd6\xd0\xce\xc4'

However, this approach is simply asking for trouble. Unless you have specific business requirements, always remember to use only UTF-8 encoding.

When formatting strings, you can test them in Python’s interactive environment—it’s convenient and fast.