As the name suggests, a computer is a machine that can perform mathematical calculations. Therefore, computer programs can certainly handle various numerical values. However, computers can process much more than just numbers; they can also handle text, graphics, audio, video, web pages, and all kinds of other data. Different types of data require different data types to be defined. In Python, the data types that can be processed directly are as follows:

Python can handle integers of any size, including negative integers. Their representation in programs is exactly the same as in mathematics, for example: 1, 100, -8080, 0, and so on.

Since computers use binary, it is sometimes convenient to represent integers in hexadecimal. Hexadecimal uses the 0x prefix followed by digits 0-9 and letters a-f (or A-F), for example: 0xff00, 0xa5b4c3d2, and so on.

For very large numbers, such as 10000000000, it’s hard to count the number of zeros. Python allows underscores (_) to be placed within numbers for readability. Therefore, writing 10_000_000_000 is exactly the same as 10000000000. Hexadecimal numbers can also be written like 0xa1b2_c3d4.

Floating-point numbers, or decimals, are called as such because when represented in scientific notation, the position of the decimal point can “float”. For example, 1.23x10^9 and 12.3x10^8 are exactly equal. Floating-point numbers can be written in standard mathematical notation, such as 1.23, 3.14, -9.01, etc. However, for very large or very small floating-point numbers, scientific notation must be used, where 10 is replaced by e. So, 1.23x10^9 becomes 1.23e9 or 12.3e8, and 0.000012 can be written as 1.2e-5, and so on.

Integers and floating-point numbers are stored differently inside a computer. Integer operations are always precise (Is division also precise? Yes!), whereas floating-point operations may introduce rounding errors.

Strings are arbitrary text enclosed in single quotes (') or double quotes ("), such as 'abc', "xyz", etc. Note that the quotes themselves are just a representation and are not part of the string. Therefore, the string 'abc' contains only the three characters a, b, and c. If the quote character itself needs to be part of the string, you can enclose the string in the other type of quote. For example, "I'm OK" contains the six characters: I, ', m, space, O, K.

What if a string needs to contain both single quotes (') and double quotes (")? You can use the escape character backslash (\) to denote them. For example:

'I\'m \"OK\"!'

The content of this string is:

I'm "OK"!

The backslash (\) can escape many characters. For example, \n represents a newline, \t represents a tab, and the backslash itself must be escaped, so \\ represents a single backslash character. You can use print() in Python’s interactive shell to see how strings are printed:

>>> print('I\'m ok.')

I'm ok.

>>> print('I\'m learning\nPython.')

I'm learning

Python.

>>> print('\\\n\\')

\

\

If a string contains many characters that need escaping, it would require many backslashes. To simplify this, Python allows strings to be prefixed with r (for “raw”) to indicate that the characters inside the quotes should be treated as-is without any escaping. Try it yourself:

>>> print('\\\t\\')

\ \

>>> print(r'\\\t\\')

\\\t\\

If a string contains many newlines, writing them all in one line with \n can be hard to read. To simplify, Python allows multi-line strings to be represented using triple quotes '''...''' or """...""". Try it yourself:

>>> print('''line1

... line2

... line3''')

line1

line2

line3

The above was entered in the interactive shell. Notice that when entering multi-line content, the prompt changes from >>> to ..., indicating you can continue typing from the previous line. Note that ... is the prompt, not part of the code:

┌─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│Windows PowerShell - □ x │

├─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┤

│>>> print('''line1 │

│... line2 │

│... line3''') │

│line1 │

│line2 │

│line3 │

│ │

│>>> │

│ │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

When you finish entering the closing triple quotes ''' and the parenthesis ), the statement is executed, and the result is printed.

If written as a program and saved as a .py file, it would be:

print('''line1

line2

line3''')

Multi-line strings '''...''' can also be used with the r prefix. Please test this yourself:

print(r'''hello,\n

world''')

Boolean values are exactly the same as those in Boolean algebra. A Boolean value can only be one of two states: True or False. In Python, you can directly use True and False to represent Boolean values (note the capitalization), or they can be the result of a Boolean operation:

>>> True

True

>>> False

False

>>> 3 > 2

True

>>> 3 > 5

False

Boolean values can be manipulated using the and, or, and not operators.

The and operator performs a logical AND operation. The result is True only if all operands are True:

>>> True and True

True

>>> True and False

False

>>> False and False

False

>>> 5 > 3 and 3 > 1

True

The or operator performs a logical OR operation. The result is True if at least one of the operands is True:

>>> True or True

True

>>> True or False

True

>>> False or False

False

>>> 5 > 3 or 1 > 3

True

The not operator performs a logical NOT operation. It is a unary operator that inverts the value, turning True into False and False into True:

>>> not True

False

>>> not False

True

>>> not 1 > 2

True

Boolean values are often used in conditional statements, for example:

if age >= 18:

print('adult')

else:

print('teenager')

Null value is a special value in Python, denoted by None. None should not be understood as 0, because 0 is a meaningful value, whereas None represents a special null state.

Additionally, Python provides many other data types such as lists and dictionaries, and also allows the creation of custom data types, which we will cover later.

The concept of a variable is basically the same as variables in middle school algebra equations. However, in computer programs, variables can hold not just numbers, but any data type.

A variable in a program is represented by a variable name. Variable names can only consist of uppercase and lowercase English letters, numbers, and underscores (_), and cannot start with a number. For example:

a = 1 # The variable a holds an integer.

t_007 = 'T007' # The variable t_007 holds a string.

Answer = True # The variable Answer holds the boolean value True.

In Python, the equals sign (=) is the assignment operator. It can assign any data type to a variable. The same variable can be assigned values repeatedly, even values of different types. For example:

a = 123 # a is an integer

print(a)

a = 'ABC' # a becomes a string

print(a)

Languages where the type of a variable is not fixed are called dynamically typed languages. In contrast, statically typed languages require you to specify the variable type when you define it. If you try to assign a value of a mismatched type, an error will occur. For example, Java is a statically typed language, and its assignment statements look like this (// denotes a comment):

int a = 123; // a is an integer type variable

a = "ABC"; // Error: cannot assign a string to an integer variable

This is why dynamically typed languages are generally considered more flexible than statically typed languages.

Please do not confuse the assignment operator = with the equality sign in mathematics. Consider the following code:

x = 10

x = x + 2

In mathematics, x = x + 2 is never true. In a program, the assignment statement first evaluates the expression on the right side (x + 2), resulting in 12, and then assigns this result to the variable x. Since x previously held the value 10, after reassignment, the value of x becomes 12.

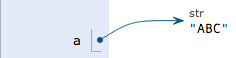

Finally, it’s very important to understand how variables are represented in a computer’s memory. When we write:

a = 'ABC'

the Python interpreter does two things:

'ABC' in memory.a in memory and points it to the string object 'ABC'.You can also assign the value of one variable to another variable. This operation actually makes the new variable point to the same data object that the original variable points to. For example, consider the following code:

a = 'ABC'

b = a

a = 'XYZ'

print(b)

What will the last line print? Will the content of variable b be 'ABC' or 'XYZ'? If interpreted mathematically, you might incorrectly conclude that b is the same as a and should therefore be 'XYZ'. However, the actual value of b is 'ABC'. Let’s walk through the code line by line to see what happens:

Execute a = 'ABC': The interpreter creates the string 'ABC' and the variable a, pointing a to 'ABC'.

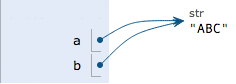

Execute b = a: The interpreter creates the variable b and points it to the same string 'ABC' that a is pointing to.

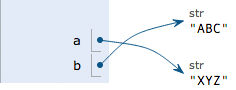

Execute a = 'XYZ': The interpreter creates the string 'XYZ' and changes the pointer of a to point to 'XYZ'. The pointer of b remains unchanged.

Therefore, the final result of printing variable b is naturally 'ABC'.

Constants are variables whose values cannot be changed. For example, the common mathematical constant π (pi) is a constant. In Python, constants are conventionally represented by variable names in all uppercase letters:

PI = 3.14159265359

However, PI is still technically a variable in Python. Python does not have any inherent mechanism to enforce that PI cannot be changed. Using all uppercase names for constants is purely a naming convention. There is nothing stopping you from changing the value of PI if you really want to.

Finally, let’s explain why integer division is also precise. In Python, there are two types of division: one uses the / operator:

>>> 10 / 3

3.3333333333333335

Division using / always results in a floating-point number, even if the division of two integers is exact:

>>> 9 / 3

3.0

The other type uses the // operator, known as floor division. When dividing two integers, the result is still an integer:

>>> 10 // 3

3

You read that correctly. Integer floor division using // always yields an integer, even if there is a remainder. To perform division that results in a floating-point number, simply use /.

Because // division only takes the integer part of the result, Python also provides a modulus operator % to obtain the remainder from the division of two integers:

>>> 10 % 3

1

Whether performing // division or taking the modulus (%) of integers, the result is always an integer. Therefore, the results of integer operations are always precise.

>>> 10 % 3

1

Whether performing // division or taking the modulus (%) of integers, the result is always an integer. Therefore, the results of integer operations are always precise.

Please print the values of the following variables:

n = 123

f = 456.789

s1 = 'Hello, world'

s2 = 'Hello, \'Adam\''

s3 = r'Hello, "Bart"'

s4 = r'''Hello,

Bob!'''

print(???) # Replace ??? with the variables to print

Python supports multiple data types. Internally, a computer can treat any data as an “object”. A variable is simply a name used in a program to refer to one of these data objects. Assigning a value to a variable (x = value) creates an association between the variable name x and the data object value.

Assigning x = y makes variable x point to the actual object that variable y is pointing to. Subsequent assignments to variable y do not affect the object that variable x is pointing to.

Note: Python’s integers have no size limit. In contrast, integers in some other languages have limits based on their storage size. For example, Java limits 32-bit integers to the range -2147483648 to 2147483647.

Python’s floating-point numbers also have no fixed size limit, but beyond a certain range, they are directly represented as inf (infinity).